On the 60th anniversary of Busy Busy World, what we can all learn from a children’s illustrator

My grandparents built a boat, and sailed around the world on it. Grandad had been a bricklayer, he understood construction and in the 1970s there was a trend for ferro-cement yachts, basically a vessel built out of reinforced concrete, a material he knew what to do with. So he and my Grandma built a yacht, in an old barn. The farmer who owned it wanted burnt down after they were done. We would visit and run around the building site, getting a lesson in how to build – seeing how the structure came together and what all the key parts did.

It was a life-sized cutaway diagram, which is probably why I loved it so much.

My Grandparents kept their word, burnt down the barn and the yacht they built was christened Phoenix, after the mythical bird born out the ashes.

Five decades later, one memory that has stayed with me from our visits to stay aboard is Grandma reading to us from a large hardback every night in the Phoenix’s galley: Richard Scarry’s What Do People Do All Day?

I’ve been thinking a lot about Scarry recently, about how he told a story and what I got from devouring everything he produced when I was a child, and then reading them to my children too. That our desire to be serious and be taken seriously sometimes gets in the way of something even more important: to be understood.

This year is the 60th anniversary of his Busy Busy World, the first of Scarry’s books to feature a double spread cutaway schematic, (of a castle in Denmark). And in 2025, it is true that everything you need to know about visual storytelling can be gleaned from the world of Richard McClure Scarry.

First published in 1968, What Do People Do All Day? is an encyclopedia of Scarry’s Busytown, the community populated by animals, which showcases every job that could be done. There is never any question that the animals represent people, they are funny and human and perilously close to disaster constantly. The gorilla in the Banana Mobile dropping banana peels everywhere. Lowly the Worm carrying a basket of eggs on his head. A delivery truck is losing a wheel and a taxi is running into a police car. And it’s about a community: people working and living together; chaotic but together.

What Do People Do All Day was where I learnt that being a reporter was exciting (and you got to carry a giant carrot pen), editors wore eyeshades and mice drove little cars (how would they reach the pedals otherwise?).

It was how I got to understand how the world works.

Say you work with data, how is this relevant? What can the work of an illustrator from Boston drawing childrens’ books teach me?

Well, here’s a list to start:

Editing: Scarry spent months researching how things worked before he illustrated them. By the time his work was committed to paper, he knew exactly what he wanted to say and how to get it across.

Accessibility: Scarry’s work is all about clarity. Anyone can understand what he is trying to say.

Simplicity: If it is doing its work properly, you take one important factor away from a visual. Scarry understood that.

Fun sticks: if you laugh at something, you will remember it.

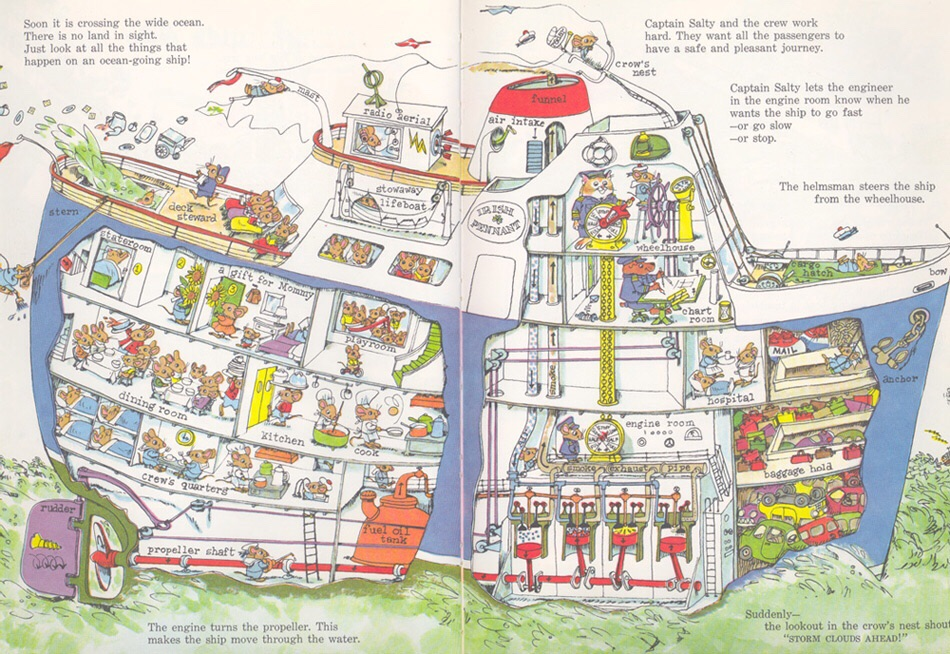

One of my favourites is this illustration: the good ship Irish Pennant.

Irish Pennant by Richard Scarry, from What Do People Do All Day, 1968

What do you see? Perhaps it is a giant cartoon of a boat with a load of visual gags. The proportions are elongated for effect and the ship’s crew are all mice lorded over by the Cat which happens to be Captain.

And yes, I see that. But there’s much more going on here. Spend time with this piece of art and you will understand the functions of a busy ship, the lifeboat (with a stowaway, naturally), what the Helmsman does, how the boat speeds up or slows down or what the rudder does or even how the engine works. Just take a look at this detail:

Isn’t that essentially everything you need to know about how an engine works? This is explanatory visualisation. It is making sure that every reader can understand a complicated concept. And it’s fun.

This is repeated throughout his work. Illustrating building a new house, with the wiring and pipes. In another illustration of a paper mill you learn how paper is made. And this may be heresy to some of you but what difference would it really make to have a hyper realistic image instead?

There’s been a reappraisal of Scarry recently: last year was another birthday – the 50th anniversary of Cars and Trucks and Things That Go, following the Pig family as they travel as a family with hundreds of different vehicles.

He understood a really important feature of explaining, the power of the visual.

In the definitive work about his life, The Busy Busy World of Richard Scarry, by Walter Retan and Ole Risom, (1997, Abrams Press), the authors write this simple truth: “Richard Scarry didn’t write his stories; he drew them”. He understood that the visual is what would stick, that the words could support that simple lesson.

I have been working with data illustrator Nigel Holmes on my new book recently and we share a love for Scarry’s work. “I read Scarry books to Rowland, my son (now 51), when we lived in England,” he recalls. “Looking back now, I don’t remember if we ever questioned why the driving wheel was on the other side of the car, but it clearly didn’t matter…what did matter was that there was so much to see, so much lovely detail, funny animal stuff as well as beautifully observed THINGS. And questions dotted around, like: ‘What do you think they are going to do?’ which were great ways to extend the stories beyond the pages of the books.”

“The drawings tell the stories, but they also suggest all sorts of possibilities, waiting for young imaginations to take them wherever they want.”

Chris Ware put it this way in the Yale Review recently: “As children, we see the world in all its detail, texture, and beauty, but when we learn the word for, as, a bird, we cease to see it as clearly or curiously as we did before we categorized and dismissed it.”

Scarry was an artist. He had got his start during the war as editor at the US Troops Information and Moral Services, stationed in Italy, where he drew maps that showed allied progress and explained how the fighting was going to over a million members of the armed services. He started producing children’s books in the early 1960s and over time you can see how those simple stories evolved into complex world creations, based on facts and figures and painstaking research. By the time of my childhood, his work was on TV, on lunchkits and in every kids’ reading collection.

Something obviously resonates about Scarry’s work today, even in the age of AI. It’s not hard to find people whose work has been heavily influenced by it: in this video, some of today’s best illustrators talk about his legacy. You can see much of his work at Richardscarry.com and there’s even been versions of his world applied to the 21st century.

On April 30, 1994, in Gstaad, Switzerland, Scarry died of a heart attack, caused by complications from esophageal cancer at the age of 74. From everything I’ve read about him, he seems thoughtful, kind and funny. I should have liked to have met him. I think he would be surprised to be featured on a website about telling visual stories written by someone who works with data.

Once, Scarry was asked if he was an educational writer disguised as a fun-man. I still think about his response. “I would say a fun-man disguised as an educator… Everything has educational value if you look for it.

“But it’s the fun I want to get across”

When was the last time you had fun with a visualisation?

Leave a comment